Scripts in Bloom, Uncovering Gardens of the Past

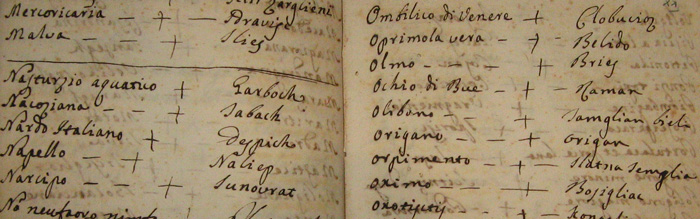

I read the plant names aloud: Faggio, Farfara, Falaride; I pause here, make note of the unfamiliar name so as to confirm it later. After close inspection, I finally decipher Finochio - fennel. The Italian garden tour I have been privileged to partake in is a unique and uncharacteristically quiet affair. I sit in a small room parsing carefully through a collection of botanical and pharmaceutical manuscripts housed in the monastery archives of the Friar's Minor in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The florid script, with long tails and broad loops flourish like the blooms that are chronicled. It is another world that I have stepped into, an extraordinary garden requiring new tools, but still as varied, mysterious and steeped in discovery as any garden plot.

It is my second consecutive morning at the monastery (I have only reached F in the plant registry) and I wait for the requested books to arrive, two at a time. Sponsored by the ARCH Foundation (Art Restoration for Cultural Heritage), I have arrived in Dubrovnik to carry out research on the Franciscan medicinal tradition in Dalmatia. The research begins purely as an archaeological endeavor, searching for manuscripts in libraries and archives, handling delicate documents and turning yellowed pages that have not seen the light of day for decades, or maybe for centuries.

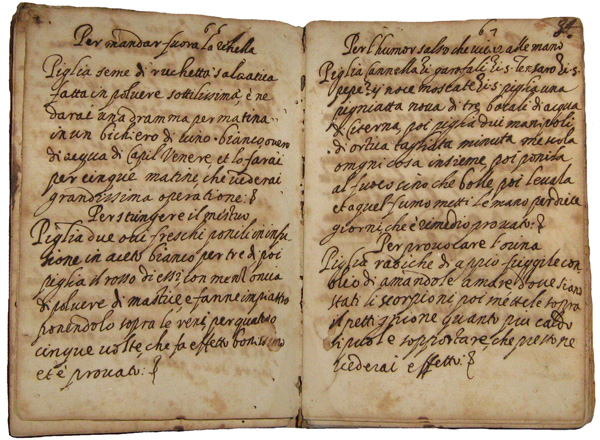

Exceedingly humble in appearance, the manuscripts are written on parchment and bound in leather. The size of prayer books, they contain no decoration, or illustration. The binding has come loose and pages have been furrowed by moths. The script is written in many hands, some with fine penmanship and others in small, barely legible script and crammed on the page like a student's cheat sheet.

Rich in text, these pages document the extensive use of plants as healing agents and provide detailed accounts of drug manufacture. The books, largely composed in the 17th and 18th century, include plant registers of hundreds of plant names, written in both Italian and Croatian, as well as manuals that collectively provide over 1000 pharmaceutical recipes.

The Friar's Minor constructed in the 14th century was, like many European monasteries by the Middle Ages, equipped with a hospital and pharmacy. Initially, tending to ailing brothers, the monks extended their care to the general public. In many cities, the only source of treatment in the time of illness was the monastic hospital. Monks became accomplished pharmacists and physicians. They studied and translated the ancient Greek texts of Dioscorides, as well as the contributions of Arabic scientists such as Avicenna. Far more than mere faithful copyists, the monks added to the pharmaceutical teachings within those texts through their own study, observation and practice.

The pharmaceutical formulations within the manuscripts of the Friar’s Minor collection follow a standard format: a list of plant ingredients, including an indication of the plant part used, followed by specific preparation instructions and details of proper drug administration.

There are recipes that ensure sustained and prolonged well-being: “Elixir for Long Life, Fantastic Pomade - Treasure for Sound Healthâ€. Panaceas prepared in every form: “Universal Liquid, Adhesive and Balsam Against Every Illnessâ€. Other remedies target specific ailments like, toothaches, headaches, hemorrhoids and tuberculosis. There are corrections, notes in the margins and recipes marked as 'tested'. Some formulations consist of just a handful of herbs, while others list over 50 ingredients, all of herbal origin.

The plant inventory is staggering. The monastery's gardens stocked the well-provisioned medicine cabinet and what wasn't grown was acquired through the extensive drug trade. Medicines were imported from Asia and the Middle East. With the discovery of the Americas and the botanical explorations of the 18th century, Europe was introduced to a new and vast repertoire of medicinal herbs.

The plants listed among the recipes that I study include aloe, juniper berries, jalapeno, saffron, boswellia, cinnamon and cloves. Given Dubrovnik's extensive trading links and close ties with Venice, procurement of the most coveted medicines was ensured.

That the plant kingdom yields a wildly diverse source of medicine may perhaps be a half-forgotten fact. There certainly has been an engaged effort in rediscovering the origins of what lies on our dinner plate, so maybe it is time to extend the same initiative to that which heals us. Digitalin, for instance, constitutes a group of drugs extracted from species of foxgloves (Digitalis spp.) that are used to treat congestive heart failure. Aspirin has its botanical roots in the bark of Salix alba, or the willow tree.

Before Pfizer, or Astrazeneca, pharmacies operated on a modest scale. Medicines were manufactured by pharmacists whose knowledge easily extended to the garden. It was a time when plants were not simply prized items of decoration and gardens offered much more than a flourishing paradise, or fragrant retreat. The names and qualities of plants and their inherent value was common knowledge. The monastery medicinal gardens were conceived and designed to reflect this understanding of the natural world.

In fact, they looked a lot like the community garden plots being cultivated in urban areas today. Raised and ordered beds. Herb gardens that included lemon balm, basil, dill, fennel, peony, rose, rosemary and rue - all traditionally used as healing agents. Rose hips were used to aid in the treatment of headaches and dill calmed indigestion. Today, these common herbs are grown to flavor the roast, or clipped for the dining table showpiece, but as these urban gardens grow, so too perhaps, will the knowledge of their distinguished and healing past.

Photo credits: Barbara Ozimec, Srdjan Todorovic